What can human and veterinary dermatologists learn from each other in the management and treatment of atopic dermatitis?

Feature

By Emily Margosian, assistant editor, December 1, 2020

In the past, a single doctor would have been called upon to care for all members of a household — including its animals. Although medicine has since diversified to include sub-specialties of sub-specialties, the idea of a “one health” concept still has merit in the understanding and management of diseases shared across both the human and animal kingdoms.

Within dermatology, atopic dermatitis (AD) has emerged as an increasingly common chronic disease in both humans and their canine companions. While AD has been observed in other animals, such as cats and horses, naturally occurring canine atopic dermatitis (CAD) offers unique translational research opportunities beyond ‘the mouse trap.’ “Canine atopic dermatitis is one of the most established large-animal models of human disease in dermatology,” said Seattle dermatologist Jennifer Gardner, MD. “Certainly from a research standpoint, collaboration really broadens our understanding of prevention, early detection, and treatment strategies for both human physicians and veterinarians.”

This month, DermWorld speaks with human and veterinary dermatologists about key areas of intra-species crossover in the presentation and pathogenesis of AD, and why the canine world may offer physicians a preview of potential treatments to come.

Overlap in clinical signs

Human and canine AD share many similarities in clinical presentation. In both, the disease tends to have an early age of onset, and targets similar areas of the body. “Most of our patients are quite itchy, and their predisposed areas are somewhat similar to commonly affected areas in people,” explained Christine Cain, DVM, associate professor of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine. “For example, flexural surfaces of the limbs, the face, paws, areas like the axillary or inguinal region.”

CAD also generally targets areas of a dog’s body where hair is most sparse or frequently moist. “In areas where the hair is less dense, allergens can more easily penetrate through the hair coat and stick to the skin to be absorbed and provoke the atopic reaction,” said Daniel Morris, DVM, MPH, professor of dermatology and allergy at the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine. “Moist areas that are frequent attack sites include the eyelids, the muzzle, and the lips.”

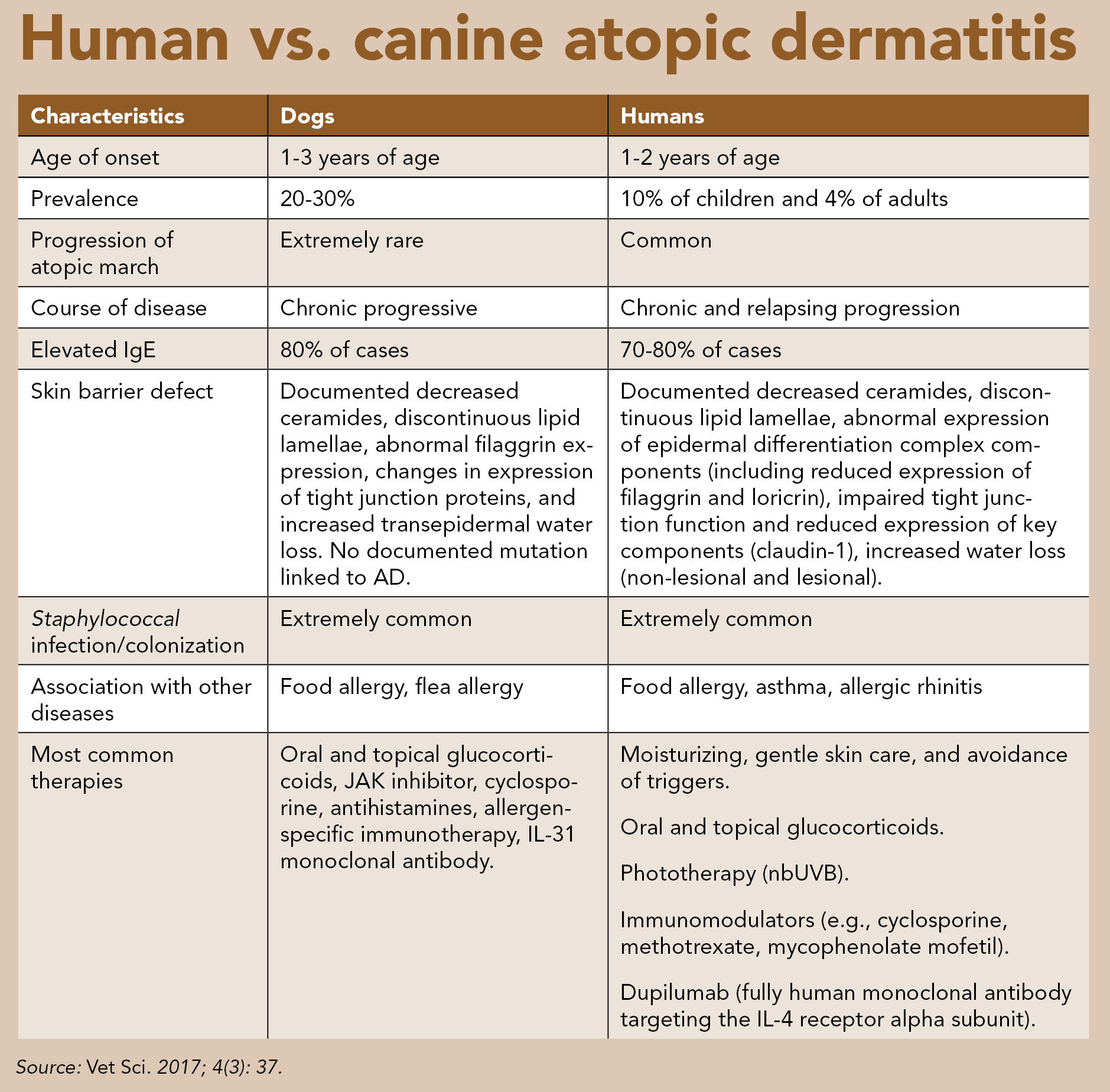

Ears in CAD patients are also often affected, as the longer ear canal in dogs may present an attractive target for allergens to enter the body. “Otitis externa is an extremely common clinical sign of atopic dermatitis, and as a result, all of the otology in veterinary medicine is done by dermatologists rather than ear, nose, and throat docs,” explained Dr. Morris. In both humans and dogs, symptoms of AD include pruritus, erythema, lichenification, and secondary infections including bacterial and yeast. “A huge part of my job as a veterinary dermatologist is managing secondary infections. Our patients, just like humans, are predisposed to secondary staph colonization and infections,” explained Dr. Cain. Although traditionally staph infections have been considered a result of AD, there is new debate on whether Staphylococcus can actually be a “cause” of AD and not simply a complicating factor that leads to exacerbation of the disease (Vet Sci. 2017; 4(3): 37).

Absence of atopic march in canine atopic dermatitis

One key difference between human and canine atopic dermatitis is that in people, AD may precede or present concurrently with other allergic diseases. This progression is referred to as the ‘atopic march,’ and is not typically seen in the canine version of the disease. “In humans, there are other atopic manifestations like asthma, allergic rhinitis, conjunctivitis, and food allergies,” said Anna De Benedetto, MD, clinical associate professor of dermatology at the University of Florida College of Medicine.

Dogs, however, tend to remain in the cutaneous stage of the disease. “In dogs you generally don’t have a clear atopic march. It’s more like an atopic eczema equivalent, and stays at the eczema level,” explained Domenico Santoro, DVM, PhD, assistant professor of dermatology at the University of Florida College of Veterinary Medicine. “We do have dogs that can develop rhinitis, conjunctivitis, and asthma, but those are much rarer compared with the human counterpart.”

Establishing a diagnosis of canine atopic dermatitis

Although a variety of clinical criteria have been considered over the years, generally a diagnosis of CAD is based on history, clinical signs, and exclusion of other pruritic diseases (Vet Sci. 2017; 4(3): 37).

“We do have sets of diagnostic criteria that veterinarians can follow to increase their confidence,” said Dr. Morris. “But the diagnosis really is one of exclusion. There aren’t many other diseases that present the way that AD does in dogs. Certainly, you can’t tell if it’s food-induced or if it’s environmental allergens or a combination of both until you do some more in-depth investigation, but there’s really no other disease process that produces the same pattern of itch that dogs get from AD.”

Understanding potential triggers and pathways of AD in humans and canines

In both humans and dogs, the cause of AD is complex and multifactorial, often a combination of genetic factors and environmental triggers. “A lot of dogs will start out with seasonal AD and progress to a more non-seasonal pattern over time as they sensitize to more and more allergens in their environment,” said Dr. Morris. “The majority of our patients are polysensitized to a number of different pollens from weeds, trees, and grasses, as well as dust mites.”

Diet too, can play a role in CAD. “Often in veterinary medicine, we use the term atopic dermatitis interchangeably to refer to a reaction from environmental or food allergens, but we certainly will investigate the possibility of a food component by doing elimination diet trials,” said Dr. Cain.

Skin barrier function

In both human and canine AD, there is evidence of interplay between skin barrier dysfunction and allergic inflammation. In people, this can result in a two-way street: skin barrier function is worsened by inflammation, and the worse the skin barrier, the more propensity toward allergic sensitization (Vet Sci. 2017; 4(3): 37). “In humans we know that both lesional and non-lesional skin present skin barrier defects, and because non-lesional skin is also affected, we think that the skin barrier defect may pre-exist before the inflammation, although we have a lot of data showing that the inflammation does disrupt the barrier,” explained Dr. De Benedetto. “When you have barrier disruption, this allows antigens and allergens to come through, and activates the immune system. So, it’s a vicious cycle between the skin barrier and the immune system.”

While the role of skin barrier abnormalities in AD has been established in human medicine for decades, investigation into the role of the skin barrier in CAD is still developing. “Skin barrier is something that I know is a big focus in human AD, with for example, filaggrin defects in humans, and there does seem to be a similar leaky skin barrier in dogs with CAD,” said Dr. Cain. “We don’t have it fully 100% worked out as far as the causes of that, or whether it is always a cause or a consequence of allergic inflammation, but it does definitely seem like they have barrier impairment that’s going to allow allergens to penetrate more readily.”

Dogs and infectious disease

Canine companions have been part of human households for centuries, and their popularity has only increased with time. According to a survey conducted by the American Pet Products Association, approximately 90 million dogs lived in U.S. homes as pets in 2018, accounting for nearly 70% of all households.

While the positive psychosocial effects of dogs have been well-documented, these furry family members can also potentially serve as vectors for viral, bacterial, or parasitic zoonotic diseases. In addition to direct contact, zoonotic disease can also be passed from canine to human through infected saliva, aerosol transmission, or exposure to contaminated urine and feces.

Popularized in both film and literature, rabies is perhaps the most notorious zoonotic disease. However, pet owners should be aware of other potential zoonoses transmitted by dogs. “I think a good example would be tinea corporis, or ringworm,” said Jennifer Gardner, MD. “That’s something that’s very easy to be shared between humans and pets in the household.”

Another highly contagious dermatologic condition passed between humans and canines is sarcoptic mange. This zoonosis is caused by an infestation of sarcoptic mites, often leading to large patches of hair loss in dogs due to chewing and scratching to relieve the intense itch. Although the mites are not able to complete their life cycle on a human host, they will similarly cause severe itching until they die.

Additionally, dogs can be colonized with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), a major cause of serious infection in human beings. Failure to detect and treat these colonized pets can result in recurrent MRSA colonization and infections in humans (Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2004;10(12):2235-2237). MRSA is typically transmitted through direct skin-to-skin contact, and households with suspected cases should practice good hygiene by keeping all wounds clean and wearing disposable gloves when touching items that may have been in contact with an infected wound.

Visit the CDC for a more comprehensive list of diseases that can spread between animals and people.

Microbiome

Microbiome diversity and its effect on atopic dermatitis is another active area of investigation in both human and canine iterations of the disease. In recent years, loss of biodiversity has been linked to the development of chronic inflammatory and allergic diseases (Vet Sci. 2017; 4(3): 37).

“We know that the composition of the microbiome in both human and canine subjects with atopic dermatitis differs in comparison to non-atopic subjects. During the flare, it becomes even more selective and less diverse, in both cases with more staph growing,” explained Dr. De Benedetto. “What we don’t know — which I think will be the big question in both — will be to really understand the relationship in pathophysiology. Does the defect in the microbiome come before the clinical change, or does it come as a consequence of the immune skin barrier defect? It may be that in some patients the skin barrier drives the inflammation in the microbiome, whereas in other patients everything starts with the microbiome change.”

Dr. Santoro agrees, “That’s the big question for atopic dermatitis in both species over the next decade — which one came first?” The close quarters shared between humans and their pets also adds an additional facet to the puzzle. “Pet owners and their dogs share the same microbiome because they live so closely together, resulting in strong similarities in the bacterial population between humans and their pets. It would be interesting to see how a shared environment between an atopic dog or atopic human could affect the microbiome in other species,” he said.

“We’re sort of in our infancy in microbiome research in veterinary medicine,” said Dr. Cain. “However, there is definitely a shift in the cutaneous, and potentially the gut microbiome, that occurs in canine patients with AD that may contribute to disease — and that we may be able to manipulate to improve the severity of their disease as well.”

Treatment options for canine atopic dermatitis

Veterinarians’ toolboxes for treating CAD contain some options that may be familiar to physicians, in addition to others that have yet to debut on the human market. “Treatment is purely multifactorial, because there are several different focus points when managing CAD,” said Dr. Cain. “We do use a lot of immunomodulatory medications; things we can use to reduce the itch, reduce the allergic inflammation. There are several therapies we have available, some a bit newer than others, and some a bit faster acting.”

Traditional therapies

“We have some older therapies. We still use things like steroids, for example, prednisone to manage acute flares,” said Dr. Cain. “Those tend to be our best anti-inflammatory medication. However, they come with a lot of long-term side effects, which is the same in humans as well. So, steroids are typically short-term options. The other medication that’s been approved for more than 15 years is cyclosporine. It’s slower-acting, but still something we use with regularity to manage our atopic patients.”

Veterinary dermatologists often prefer oral or systemic therapies as opposed to topicals when treating atopic dermatitis due to the logistical challenges of treating patients covered in fur. “Often human dermatologists ask, why are you only using cyclosporine so flippantly to treat atopic dermatitis in dogs and cats? Why don’t you use more topical therapies? The answer is that our patients are covered with such dense hair coats, we can’t get topical therapies down to the skin where they need to go,” explained Dr. Morris. “So, we do use a fair amount of cyclosporine in our more severe patients. The real advantage is that it controls the inflammation well enough in most dogs and cats to prevent recurrent secondary infections. If we end up failing with the IL-31 inhibitors, the JAK1, and the monoclonal, then usually our final hurrah is cyclosporine.”

“Often human dermatologists ask, why are you only using cyclosporine so flippantly to treat atopic dermatitis in dogs and cats? Why don’t you use more topical therapies? The answer is that our patients are covered with such dense hair coats, we can’t get topical therapies down to the skin where they need to go.”

Immunotherapy

Another key difference between veterinary and human dermatology’s treatment of atopic dermatitis is the former’s use of allergen-specific immunotherapy. “Something we do a fair bit of is allergen testing, followed by either subcutaneous shots or sublingual drops, using those specific allergens that the patients react to. I know that’s something that’s done for allergies in humans, like rhinitis and asthma, but I don’t know how much it’s used for AD,” said Dr. Cain.

“We rely a great deal on allergen-specific immunotherapy for treatment,” agreed Dr. Morris. “Physician dermatologists rarely, if ever, use allergen-specific immunotherapy for treatment of their patients, but we very commonly do because it works for a significant portion of our patient population — a 60% success rate in dogs, cats, and horses, which is nothing to sneeze at.” Despite the positive success rate, the slow speed of immunotherapy in animals can make compliance among human caretakers difficult at times. “Sometimes it takes 12 months or more for some individuals — especially horses — to show a good response,” said Dr. Morris. “It can be hard to convince pet owners to keep the faith and give it the old college try for a full year instead of giving up in frustration if it doesn’t work right away in their pets.”

Dr. Morris theorizes that veterinary dermatologists’ preference for immunotherapy in contrast to their counterparts in human medicine is the result of different areas of focus within the fields. “On the human side, allergists do all the intradermal testing, prick testing, and immunotherapy mainly for respiratory allergy and asthma. And for whatever reason, the dermatologists just didn’t do the same for atopic dermatitis,” he said. “In our specialty, the allergists are the dermatologists. So, we’re not only dermatologists, we’re also allergists and otologists. Those three specialties got rolled in together in veterinary medicine very differently than they did human medicine. I’ve always wondered if that was why there’s so little allergen-specific immunotherapy done for AD in people.”

“If you can make monoclonals for dogs at such an affordable price, then there’s got to be something wrong; the research and development pipeline can’t be that different. It’s hard to imagine why a drug that’s $55 a month in a dog is $10,000 in a person.”

Emerging treatments

As the use of biologics has emerged over the past 30 years, the veterinary world has had some early access to certain interventions not yet available in human medicine. “One option available to us is lokivetmab, a monoclonal antibody for IL-31, which is probably one of our most targeted anti-itch therapies,” said Dr. Cain. “It tends to reduce itch within a very short period of time, often within 24 hours or less, and is something we can use even in younger dogs where we’re limited in some of our other therapies. I think there’s something similar in the works for humans, but we definitely had this available for dogs first.”

“This monoclonal targets only IL-31, and binds to and inhibits its ability to bind to nerve endings in the skin. When IL-31 binds to nerve endings, it triggers the sensation of itch. For some dogs, inhibiting just IL-31 is all they need to have incredible relief of itch,” explained Dr. Morris. “So clearly for some subset of dogs with AD — and I would assume the same will be true with people — IL-31 plays such a huge role that just inhibiting it alone is enough to bust the itch.”

Despite its success at relieving itch, lokivetmab does have some limitations. One is its limited anti-inflammatory properties — not that the patients are always bothered, suggests Dr. Morris. “Dogs are happy as clams even if they still have a rash. They don’t care. The bigger issue is that it doesn’t do a good job at calming the skin enough to prevent recurring infections in the subset of dogs that tend to get secondary infections over and over. But for dogs who don’t, it can be an excellent long-term therapy, and seems to be quite safe which is always a concern with any immunoregulatory drug.”

Another well-established treatment in veterinary medicine is oclacitinib, the first JAK inhibitor approved in the United States and Canada for the treatment of atopic dermatitis in dogs. “Oclacitinib is selective for the JAK1 pathway, so that’s going to affect or down-regulate signaling of pro-inflammatory and pro-itch cytokines,” explained Dr. Cain. “That’s another thing we had available on our side first, which was kind of exciting. Obviously, these new therapies aren’t effective for every patient, but they’re a really nice tool to have in the toolbox for managing itch.”

One step ahead of the human treatment pipeline?

According to Dr. Cain, although veterinarians aren’t used to having first access to new therapies over their human counterparts, treatments for AD have proved to be one of the exceptions. “As an atopic human myself, my allergist has been fascinated by some of the things we’ve had available before they were on the market in human medicine, which is almost never the case,” she said. “I think it’s just much easier to go through clinical trials and to have drugs approved for veterinary use. That may be why it’s just been a little bit faster on our side of things to get these drugs on the market.”

“While we may not have all the things they’re using approved for humans just yet, you can look to see what veterinarians are doing and what they’re using, and get a little peek into the future for what might be coming down the pipeline eventually for our patients,” said Dr. Gardner. “It’s important to understand what’s being used in the animal world because it affects our environment and human health as well.”

Cost differences between human and canine drugs

One question Dr. Morris often fields from colleagues in human dermatology is why the huge cost differential across different markets for essentially the same drug? “The answer is usually, you’re at the mercy of insurance companies, and we aren’t,” he said. “The companies producing veterinary drugs know they aren’t going to sell a bit of product unless they make them accessible to pet owners. In the human market, they can get away with much higher prices because a third party will pay for it.”

While Dr. Morris acknowledges that the regulatory requirements for getting a human biologic approved may carry additional costs to manufacturers, “If you can make monoclonals for dogs at such an affordable price, then there’s got to be something wrong; the research and development pipeline can’t be that different. It’s hard to imagine why a drug that’s $55 a month in a dog is $10,000 in a person.”

The power of collaboration

While human and veterinary medicine have traditionally been siloed, that paradigm has recently begun to shift, suggests Dr. Gardner. “I’m constantly thinking about the shared environment and what types of companion animals or pets are within that environment,” she explained. “When I see certain conditions in human skin, I consider at times calling a patient’s family veterinarian to talk to them about what they’re seeing, any potential links, and how we can maybe control the environment or the risk factors. It’s an important aspect that you can’t ignore. Otherwise you’re just putting a bandage over the problem by treating what you see in front of you in your own clinic on their skin.”

Dr. De Benedetto agrees that despite the difference in choice of patient, human and veterinary dermatologists have much to learn from one another. “We really treat the same diseases with some variations. By working together, we can speed up the process. One great example is that dogs had the JAK1 inhibitor first, and it was probably an important push for human medicine to be able to apply the same drug,” she said.

The same goes both ways, according to Dr. Santoro. “We certainly look at what human dermatologists and allergists are doing and apply it to our patients,” he said. “It really expedites and improves our overall knowledge of atopic dermatitis in both species.”

Dog breeds commonly predisposed to atopic dermatitis

While canine atopic dermatitis is not limited to any particular breed, the disease can be observed more frequently in certain types of dogs. These can typically include:

- Retrievers (Golden Retrievers, Labrador Retrievers, etc.)

- Terriers (West Highland White Terriers, etc.)

- Bully breeds (Mastiffs, English/American Bulldogs, American Pitbull Terriers, Staffordshire Bull Terriers, etc.)

While it is not yet fully clear why certain dog breeds are more predisposed to developing atopic dermatitis, genetics may play a role, suggested Christine Cain, DVM. “Certainly, the gene pool for some of our purebred dogs is rather shallow, which can cause complications, although the genetics are not simple,” she explained. “There are probably different phenotypes of the disease according to breed, so we’re just at the beginning of figuring out the genetics of the disease in different breeds. However, we can certainly see atopic dermatitis in any type of dog.”