By Warren R. Heymann, MD

April 7, 2021

Vol. 3, No. 14

If your practice bears any resemblance to mine, a significant portion of your schedule is devoted to patients following up because of their history of melanoma. Prior to seeing the patient, our medical assistant runs through a focused review of symptoms — Have you noted any new or changing moles, lumps or bumps? Headaches? Shortness of breath? Weight loss? “Changes in vision” is included. Honestly, I never gave that much thought, thinking that it reflected a concern for ocular melanoma. I now have a new perspective, having just learned of melanoma-associated retinopathy (MAR).

Paraneoplastic syndromes in neuro-ophthalmology may affect afferent and efferent visual symptoms. Reduced visual acuity from retinal degeneration, alterations in melanocyte proliferation and uveal thickness, or acquired nystagmus may be observed. Ocular motor abnormalities related to paraneoplastic syndromes range from uncontrolled eye movements (opsocionus) or from neuromuscular junction disease. Serologic identification of specific antibodies may be confirmatory. Treatment of these paraneoplastic syndromes is based on targeting the cancer itself while treating with corticosteroids, other immunosuppressive agents [i.e., methotrexate, IVIG], or plasma exchange. MAR is a specific variant of cancer-associated retinopathy (CAR), that may be associated with small cell lung cancer, breast, colon, prostate, ovarian, endometrial, cervical, bladder, thyroid, thymus, pancreatic, and hematologic malignancies. (1)

CAR is defined as an autoantibody-driven retinal degeneration that is not caused by tumor metastasis. The prevailing hypothesis is that antiretinal antibodies in high titers penetrate the retina, affecting function of the target antigens, thereby causing retinal dysfunction and degeneration. A dozen antiretinal antibodies have been associated with CAR, and because of a lack of restriction of autoantibodies to any one antigenic protein or retinal cellular localization, screening for an antibody CAR marker is challenging. (2) The primary disease associated antigen in MAR is TRPM1 (transient receptor potential melanopsin 1). (1) The shared neuroectodermal lineage of melanocytes with retinal cells allows these autoantibodies, directed against the bipolar cells of the retina, to destroy retinal cells with resultant photoreception and signal transduction dysfunction and visual disturbance. Early recognition of MAR is essential, as it can precede the diagnosis of primary or metastatic melanoma, and early treatment can diminish the risk of irreversible immunological damage to the retina, with improved visual outcomes.

According to Elsheikh et al, MAR is classically defined as a triad of: (a) symptoms of night blindness (nyctalopia), positive visual phenomena, or visual field defects; (b) electroretinography (ERG) findings of a reduction in b‐wave amplitude (ERG is an extremely sensitive technique for detecting abnormalities associated with MAR, with the typical pattern being a normal photopic [bright light] response and a markedly reduced scotopic [dim light] response); and (c) the presence of serum autoantibodies targeting retinal bipolar cells. MAR can develop from 2 months to 19 years after primary MM, with a typically shorter latency period in the context of metastatic MM (1 month – 15 years). (3)

An example of MAR signaling metastatic melanoma is the case of a 74-year-old man with a T1a melanoma of his left arm (Breslow thickness 0.77mm), who presented 4 years later complaining of shimmering lights in his entire field of vision for 5 weeks. MAR was suspected and confirmed by ERG. Antiretinal antibodies were elevated and a PET-CT scan was positive for a right lower lobe mass and hilar adenopathy, proven to be metastatic melanoma by endobronchial biopsy. (4)

There are other circumstances where MAR may be observed. A case has been reported in a 63-year-old man with a conjunctival melanoma of the left eye who developed right monocular vision loss. (5) Immune checkpoint inhibitors used to treat melanoma may induce or exacerbate MAR. (3) Audemard et al reported the case of a 70-year-old woman, with a history of both choroidal and cutaneous melanomas. She presented with MAR and vitiligo concurrent with cutaneous melanoma relapse as she was treated with the anti-CTLA-4 antibody ipilimumab. (6)

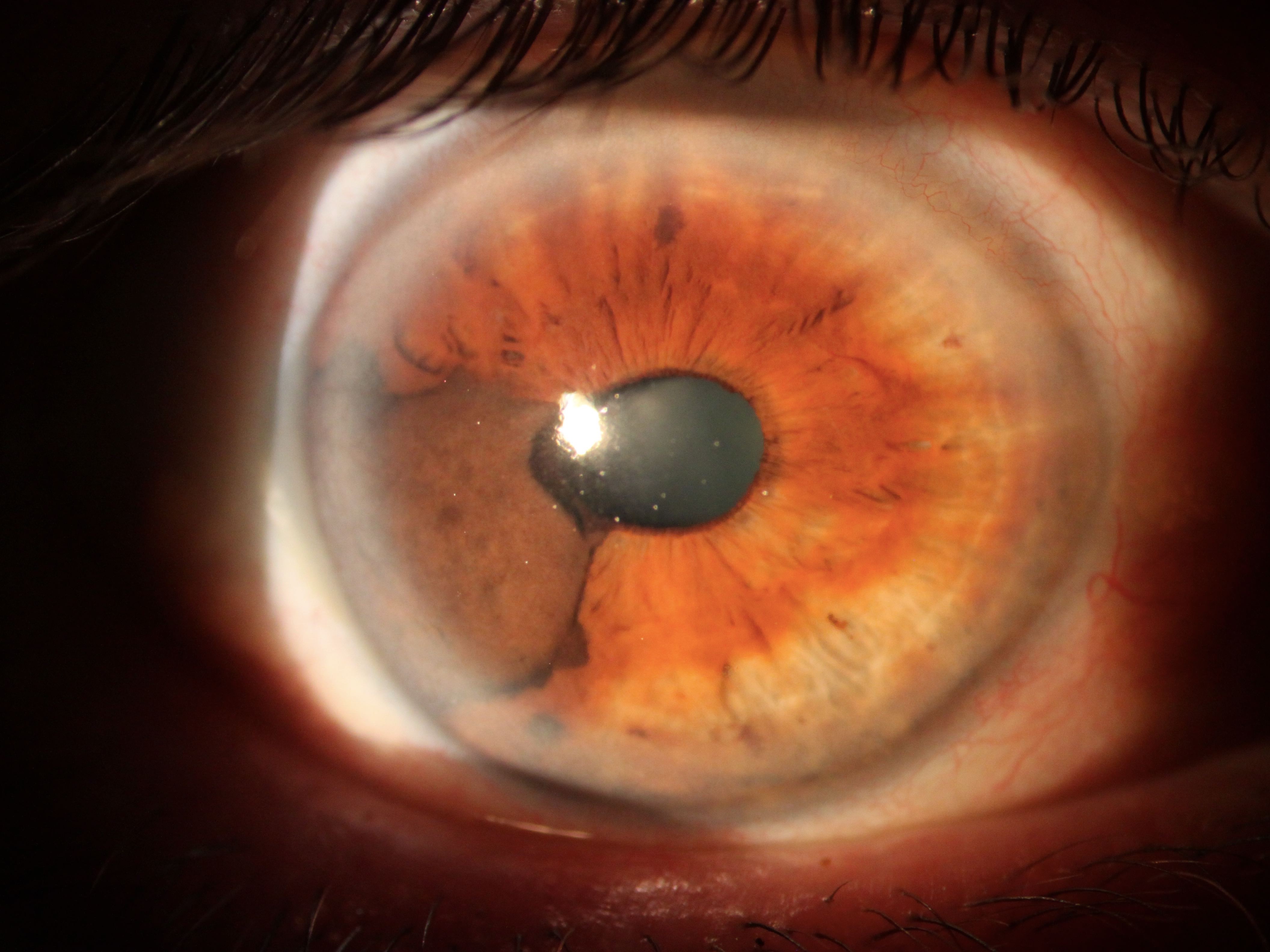

As for ocular melanoma (OM), it is the second most common type of melanoma after cutaneous melanoma and is the most common primary intraocular malignant tumor in adults. Patients with light skin, lentigines, atypical nevi, light eye color, iris nevi, and a history of ultraviolet exposure are at risk. The most common OM are uveal melanomas; others include conjunctival, choroidal, iris, and ciliary body melanomas. Common symptoms include blurry vision, visual field defects, flashing lights, redness, irritation, pain, or pressure. Therapy includes radiation, laser photocoagulation, gamma knife stereotactic radiosurgery, chemotherapy, local surgical resection, or enucleation. The ultimate prognosis depends on the size of the lesion. Ocular melanoma metastasizes hematogenously at an early age, virtually always to the liver. (7)

Point to Remember: Melanoma-associated retinopathy is a rare paraneoplastic phenomenon that may be observed in patients with primary or metastatic melanoma. Dermatologists should inquire about visual disturbances in their patients with a history of melanoma, as early recognition and treatment of MAR may help preserve vision.

Our expert’s viewpoint

Michael E Ming, MD, MSCE

Associate Professor of Dermatology at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania

Although melanoma-associated retinopathy (MAR) is very rare, I had a melanoma patient whose metastases were discovered because of a workup initiated by his ophthalmologist for MAR. In this particular case, the patient was an 81-year-old man who had a 1mm melanoma, non-ulcerated but with 2 mitoses/mm2, on his left shoulder 5 years earlier. He had new vision changes that led to concern for MAR, and a resultant PET/CT showed multiple liver metastases in this otherwise asymptomatic patient. Because of the ophthalmologist’s awareness, the patient was started on systemic immunotherapy much more quickly than would have happened otherwise. Close coordination of our care with a patient’s ophthalmologist and other health care providers can lead to better outcomes for patients.

- Gordon L, Dinkin M. Paraneoplastic syndromes in neuro-ophthalmology. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2019; 25:1401-1421.

- Adamus G. Champaigne R. Yang S. Occurrence of major anti-retinal autoantibodies associated with paraneoplastic autoimmune retinopathy. Clin Immunol 2020; 210:108317.

- Elsheikh S, Gurney SP, Burdon MA. Melanoma-associated retinopathy. Clin Exp Dermatol 2020; 45: 147-152.

- Heberton M, Azher T, Council ML. Metastatic cutaneous melanoma presenting with melanoma-associated retinopathy. Dermatol Surg 2019; 45:606-607.

- Evoy F, Lafortune J. First case of melanoma-associated retinopathy with conjunctival melanoma. Can J Opthalmol 2020 Feb 21. pii: S0008-4182(18)31039-1. doi: 10.1016/j [Epub ahead of print].

- Audemard A, de Raucourt S, Miocque S. Melanoma-associated retinopathy treated with ipilimumab therapy. Dermatology 2013; 227: 146-149.

- Patel DR, Patel BC. Cancer, ocular melanoma. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL). StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan.

All content found on Dermatology World Insights and Inquiries, including: text, images, video, audio, or other formats, were created for informational purposes only. The content represents the opinions of the authors and should not be interpreted as the official AAD position on any topic addressed. It is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.