By Warren R. Heymann, MD

Dec. 9, 2020

Vol. 2, No. 48

In a utopian dermatology practice, an astute dermatologist will establish an exacting differential diagnosis, biopsy the most revealing lesion utilizing a technique providing an optimal sample, label the bottle correctly, fill out a requisition form with care and ample clinical information, and have the specimen arrive expediently at the laboratory where perfect sections are prepared for a dermatopathologist who is as astute as the clinician.

Astoundingly, this process holds true most of the time, but occasionally errors occur in any of these steps, yielding an unsatisfactory result.

As a dermatopathologist, I will initially scan slides attempting to render a diagnosis without clinical information. I then look at the requisition form for the clinician’s impression, with the ultimate goal of affording precise clinical-pathologic correlation. Often, I will look at a specimen and see nothing but “normal” skin — that is when I need help to guide me. When a clinician provides accurate clinical information, I can then look for appropriate subtle clues that otherwise might have gone unnoticed.

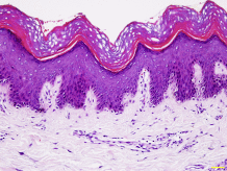

Brownstein and Rabinowitz coined the phrase “invisible dermatoses” for clinically significant skin disorders with histology resembling normal skin. This group of dermatoses accounts for almost 10% of all skin biopsies. Since their initial report, the number of invisible dermatoses has greatly expanded. If there is absolutely no clinical information to guide the dermatopathologist, one could follow the authors’ strategy of a systematic approach to the slide, first examining the epidermis for fungi, cornoid lamellae (disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis), and absence of the granular layer (dominant ichthyosis vulgaris). The dermis is then studied for hyaline deposition (macular amyloidosis), mast cells, microfilaria, dermal melanocytosis, silver granules of argyria, and absence of sweat glands (anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia). Deeper sections are often revealing. Special stains could be ordered to uncover conditions like anetoderma and nevus elasticus. Direct immunofluorescence and immunohistochemistry may be valuable in select cases. Comparison of the specimen with normal skin may disclose atrophoderma, lipoatrophy, vitiligo, or a café au lait macule. Importantly, technical problems should be addressed, including sampling errors and mix-up of specimens, either by the clinician or the laboratory. (1,2)

Alhumidi et al performed an analysis of 81 skin cases selected from a tertiary hospital pathology department diagnosed by general pathologists as “no specific diagnosis,” or “minimal pathologic changes.” These cases were subsequently reviewed and diagnosed by a dermatopathologist — the diagnoses were compared with the original diagnoses. Out of the 81 cases, 43 cases (53%) were reported by the dermatopathologist to have a specific diagnosis while 38 cases (46.9%) remained nonspecific. Both inflammatory and neoplastic diagnoses of potential clinical significance were made in the first group of 43 cases. The remaining 38 cases with nonspecific results were due to an inadequate biopsy specimen (such as fragmentation of the specimen, crush artifact, or superficial biopsies for alopecia and panniculitis), inactive lesions, or inadequate clinical data. The authors concluded that invisible dermatoses are difficult cases for general pathologists and dermatopathologists to diagnose. Minor, subtle changes on a skin biopsy do not mean it is disease‐free.

In any field of endeavor, I expect (and hope!) that those with advanced training and specialized knowledge would perform better than those without such training. Board-certified dermatologists should be better dermatologic diagnosticians than primary care physicians, just as board-certified dermatopathologists should be more skilled than general pathologists in interpreting skin specimens. The key for any clinician — in any discipline — is knowing one’s limitations (“knowing what you don’t know”) and asking for assistance when not sure. Every day I’m perplexed clinically and at the microscope. I’m always seeking second opinions when I am in doubt.

Of all the potential steps in the diagnostic cascade that could go awry, the most easily fixable is for clinicians to provide relevant, accurate information on the requisition form. In a survey completed by 598 members of the American Society of Dermatopathology, 42.7% of respondents rated the quality of clinical information provided by clinicians as fair or poor, thereby adversely impacting diagnostic performance, efficiency, and ultimately patient care quality and safety. (4)

Despite the rumblings of electronic medical records (EMR) and burnout, our integrated EMR has greatly improved my dermatopathology experience. When not satisfied with the requisition form, all I need to do is click on the patient’s record, and (when available) look at a clinical image. What a delight!

There is another simple way of improving the process — expunging the term “rule-out ____” (fill in the blank — usually basal cell skin cancer, squamous cell carcinoma, etc.) from the requisition form. In his refulgent essay “Ruling Out the Diagnosis,” Michael Bigby asserts: “Seeing ‘rule out’ written in the clinical information of pathology requisitions drives me completely crazy. The problems with writing ‘rule out’ as the clinical information for the pathologist are as follows: (1) more often than not it does not express the actual intent of the clinician; (2) the pathologist cannot determine the clinician’s intent; (3) it is used in situations in which the result ‘cannot’ be used to ‘rule out’ the suspected diagnosis; (4) it robs students and residents of an exercise that will help them improve their physical diagnostic skills and learn dermatology; and (5) it ignores clinical epidemiologic principles of using diagnostic tests.” (5) Abdou et al have demonstrated that the term “rule out” in requisition forms may cause diagnostic delays (because of unnecessary sections and stains), especially in non-integrated dermatopathology practices. (6)

Point to Remember: By working carefully at every step in the dermatopathology process, with appropriate communication between the dermatologist and dermatopathologist on the requisition form (and even personal discussion of the case!), “invisible dermatoses” may reveal their identity, yielding something from nothing.

Our Expert’s Viewpoint

Jason B. Lee, MD

Clinical Vice Chair

Director, Jefferson Dermatopathology Center

Director, Residency and Dermatopathology Fellowship

Director, Jefferson Pigmented Lesion Clinic

Jefferson University Hospitals

The observation by Alhumidi et al. that formally trained dermatopathologists are able to diagnose skin diseases with more specificity than general pathologists should be no surprise. The study confirms that general pathologists frequently have difficulty diagnosing a group of skin diseases with subtle histopathologic changes also known as “invisible dermatoses” that include vitiligo, urticaria, tinea versicolor, macular amyloidosis, and telangiectasia macularis eruptiva perstans. Experienced dermatopathologists are better able to recognize relevant histopathologic findings and frame the problem more appropriately than neophytes or those who are less experienced, while taking into account the biases of diagnostic momentum and confirmatory bias that may lead him or her astray. In the interest of the patient, clinicians have a fiduciary role to provide sufficient and appropriate tissue sample and clinical information without leading to ensure that the dermatopathologist has the best chance at arriving at the correct diagnosis, particularly when the stakes are high. I once (at least it’s the only one that I know of) missed a desmoplastic melanoma, a feared diagnosis by all dermatopathologists. I did not miss the diagnosis on the primary biopsy sample, but on the re-excision. I received a routine large melanoma excision, which I signed out as Scar and No Residual Neoplasm, my usual sign out for the countless excisional specimens with no residual lesion. A year and a half later, when I was asked to review the desmoplastic melanoma excisional specimen, the bland spindle cells in the dermis interpreted initially by me as fibroblasts were no longer, but were bland spindle cells of residual desmoplastic melanoma. Though I am culpable of the mistake, a simple addition of the word desmoplastic in the requisition form would have alerted me to consider the bland spindle cells in the dermis as residual desmoplastic melanoma and not a scar. And so, I strongly agree with Dr. Heymann’s point to remember that appropriate communication between dermatologist and dermatopathologist on the requisition form is a crucial component in the dermatopathology diagnostic process for “invisible dermatoses” and not so “invisible dermatoses.”

- Khan K, Mavanur AA. Longitudinal melanonychia. BMJ Case Rep 2015 Dec 10;2015. pii: bcr2015213459. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2015-213459.

- Baran R, Kint A. Onychomatrixoma. Filamentous tufted tumour in the matrix of a funnel-shaped nail: A new entity (report of three cases). Br J Dermatol 1992; 126: 510-515.

- Okon LG, Saeid N, Schwartz L, Lee JB. A case of onychomatricoma: Classic clinical, dermoscopic, and nail clipping histologic findings. J Am Acad Dermatol 2017; 76 (2S1): S19-S21.

- Miteva M, de Farias DC, Zaiac M, Romanelli P, Tosti A. Nail clipping diagnosis of onychomatricoma. Arch Dermatol 2011; 147: 1118-1119.

- Kallis P, Tosti A. Onychomycosis and onychomatricoma. Skin Appendage Disord 2016: 1: 2019-212.

- Nguyen CV, Moshiri AS, Council ML, Rosman IS, Rubin AI. Pigmented onychomatricoma mimicking nail unit melanoma. J Cutan Pathol 2019; 46: 895-897.

- Baran R, Perrin C. Bowen’s disease clinically simulating an onychomatricoma. J Am Acad Dermatol 2002; 47: 947-949.

- Isales MC, Haugh AM, Bubley J, Zarkin S. Pigmented onychomatricoma: A rare mimic of subungual melanoma. Clin Exp Dermatol 2018; 43: 623-626.

- Baran R, Kechijian P. Hutchinson’s sign: A reappraisal. J Am Acad Dermatol 1996; 34: 87-90.

All content found on Dermatology World Insights and Inquiries, including: text, images, video, audio, or other formats, were created for informational purposes only. The content represents the opinions of the authors and should not be interpreted as the official AAD position on any topic addressed. It is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.